Hollie Venn, chief executive of Sheffield Women’s Aid, shares her thoughts on the Feminist Leadership session at our Summer Conference in the context of her career, studies and the work of her organisation.

Prior to the webinar for the feminist leadership discussion, I felt excited to hear the participants views and thinking, not only as a previous cohort member for the feminist leadership course, but having recently completed an MSc in Leadership. My dissertation focus was based upon women’s lived experiences of leadership, so this webinar filled me with excitement to hear how women understood and interpreted “feminist leadership”.

Hearing that WRC’s feminist leadership programme is its most popular was of no surprise! Tebs and Evelina are clearly dedicated to empowering women to harness their feminist leadership skills, and this is translated to a clear framework for the training.

They both talked of their aspiration to see women walking the talk, and challenging the androcentric norms of leadership theory and practice through offering a dedicated space for women to reflect on their leadership journeys – no matter where they may be in them.

Having this dedicated space is often deemed a luxury, but hearing each participant talk about how their group valued this intimate space to be vulnerable and explore the topic was heart-warming. It reaffirmed why these opportunities are so valuable for women. It also reminded me of the power and confidence that can be achieved when participating in such opportunities.

The first speaker, Lioness Tamar of the Lioness Circle, shared how her very personal experiences had given her pause for reflection on where feminism intersected with black and minoritised women’s histories. She had originally thought it was a distraction from such thinking.

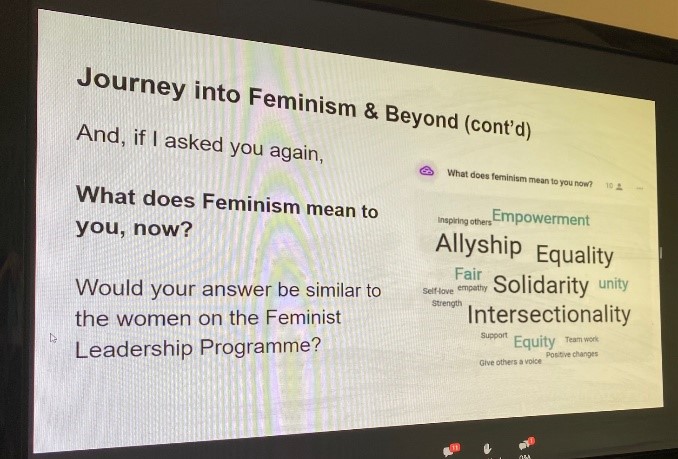

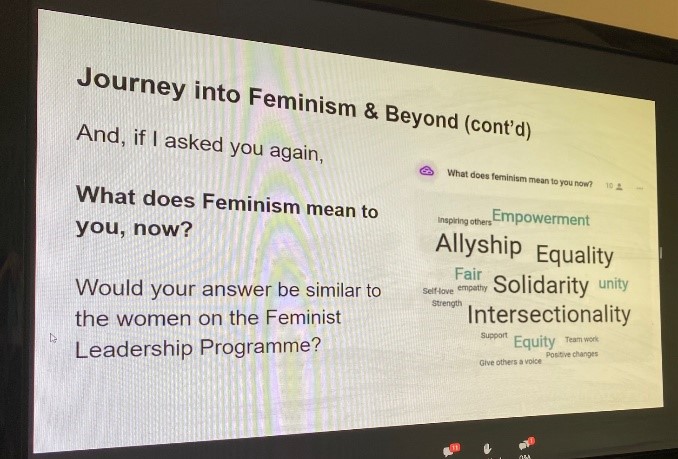

The programme helped Lioness Tamar realise that feminism not only evokes strong responses about what it is and means, but enables her to challenge her own thinking. This is true of feminism and around how when feminism centres intersectionality, it lifts us all up. Her challenge to us was to analyse “what does feminism mean to you?”

Up next, Olivia shared what I know from my own dissertation findings to be a very common barrier for women – imposter syndrome! Hearing Olivia’s description of imposter syndrome as a barrier to asking for help and sharing ideas felt like the polar opposite to how we, in the women’s sector, seek to be. But, as Olivia clearly identified, lacking the psychological safety to be honest has a very real impact.

Olivia shared how we need an arsenal of emotional intelligence weaponry in our “toolbox” as feminist leaders. This helps us to respond to leadership challenges. “We are not here by mistake” – no Olivia we certainly aren’t and we deserve our place at any table!

At this point in the presentations, it was infectious to hear the value women had received from attending the training. They were all, in their own ways, analysing the concepts of both leadership and feminism with a real desire to consider how both should be applied to their work practices in a joined-up way. These thoughts offered personal reflections for me, too. It made me realise that I have often viewed them as separate entities, when in fact they are congruent.

Nish and Adeola challenged us to wonder what a feminist leader looks like, against a backdrop of “leadership” often being considered/portrayed as white, male and a hierarchal domain. I would suggest these assumptions do have weight. My own MSc research findings show very little leadership theory has considered women’s leadership and there’s even less research in the environments women tend to inhabit. If we don’t ask women, we don’t know!

As Nish and Adeola signposted us towards, and in the same way that Olivia identified, the ability to demonstrate emotional intelligence is crucial for feminist leaders. It allows us the ability to really reflect and think about how we are leading.

The VAWG sector has strong historical inceptions around collaborative working and findings ways of placing those we support at the heart of what we do. While the operating environments we inhabit have evolved, it’s crucial we retain those fundamental frameworks of asking ourselves “what does feminist leadership look like” and “how can we be allies to each other?”

Lastly, Sidra reflected upon the very real dilemma of what feminist leadership looks like in an organisation. I know from my own leadership research this can have different guises when working in a dedicated VAWG service, rather than a generic organisation.

What is probably lost in the latter is the understanding of feminism and how that is inextricably interwoven with how services are led. Sidra rightly highlighted how organisations’ expressions of power are articulated – it’s the “way things are done around here” – who makes the drinks, who chairs meetings, etc.

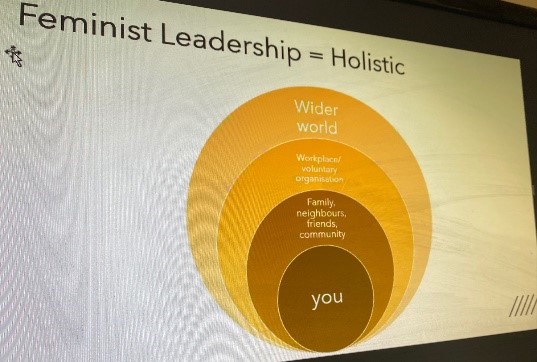

Equally, what messages do they send? Sidra shared the ground rules her group constructed, too. What I thought when seeing this was how much these capture really effective feminist research principles! Sidra ended on a slide that showed how the “ripple” effect of feminist leadership works in a holistic way. Much like Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the slide demonstrated how this starts with the individuals and can have a “ripple” effect out to the wider world.

A colleague and I attended this event as seasoned feminist leaders, and we both came away feeling so enthused by each participants discussion and excited for their leadership journeys as feminists.

It was obvious the programme had enhanced all of the women’s learning and understanding of not just leadership but feminist leadership. From a personal perspective it was fantastic to see women embrace leadership discussions in the way they had. My hope would be that this programme can continue as it seems to have captured the “teach 1 person, and you teach a village” ethos.

Visit Sheffield Women’s Aid’s website and follow on Twitter.